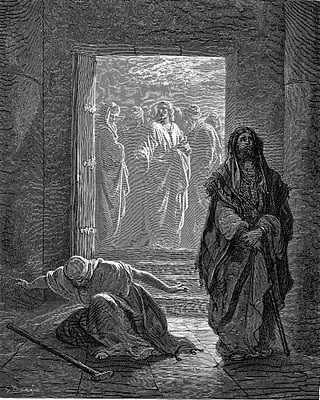

The Pharisee and the Publican (Gustave Doré)

'Conspicuous Compassion: Why sometimes it really is cruel to be kind'

by Patrick West is published by Civitas (London). Chapter 1.

Conspicuous Compassion

‘Observe how children weep and cry, so that they will be pitied the thirst for pity is a thirst for self-enjoyment, and at the expense of one’s fellow men’.

Friedrich Nietzsche

‘Human, All Too Human’, 1878

WE live in an age of conspicuous compassion. Immodest alms-giving may be as old as humanity—consider the tale of Jesus rebuking the self-exalting Pharisee—but it has flowered spectacularly of recent. We are given to ostentatious displays of empathy to a degree hitherto unknown. We sport countless empathy ribbons, send flowers to recently deceased celebrities, weep in public over the deaths of murdered children, apologise for historical misdemeanours, wear red noses for the starving of Africa, go on demonstrations to proclaim ‘Drop the Debt’ or ‘Not in My Name’. We feel each other’s pain. In the West in general and Britain in particular, we project ourselves as humane, sensitive and sympathetic souls. Today’s three Cs are not, as one minister of education said, ‘culture, creativity and community’, but rather, as commentator Theodore Dalrymple has put it, ‘compassion, caring and crying in public’.

This book’s thesis is that such displays of empathy do not change the world for the better: they do not help the poor, diseased, dispossessed or bereaved. Our culture of ostentatious caring concerns, rather, projecting one’s ego, and informing others what a deeply caring individual you are.

It is about feeling good, not doing good, and illustrates not how altruistic we have become, but how selfish. Consider the growth of looped empathy ribbons. Since their appearance in the 1990s, donations to charities have not actually grown. Far from ‘raising awareness’, ribbons serve merely to inform one’s peers how terribly concerned one is about Aids, cancer sufferers or children with leukaemia. We live in a generation that is fond of signing web petitions to ‘stop war’—petitions that do nothing of the sort. It has manifested itself in that slogan ‘Not In My Name’, a phrase that suggests that today’s ‘anti-war’ protesters are no longer concerned with stopping conflict, but merely announcing their personal disapproval of it. ‘Drop the Debt’ say others, forming human chains around G8 meetings, shoving in our faces photographs of emaciated Ethiopians. This phenomenon is not some harmless foible. Outlandish and cynical displays of empathy can bring about decidedly ‘uncaring’ consequences. In terms of the Third World, ‘dropping the debt’ may not help starving Africans at all. It may make their lives worse by rewarding their kleptocratic governments, freeing up their budgets to buy more guns to perpetuate their pointless wars. We like to be spotted giving alms to beggars, yet such an action can have the contrary result. Most beggars spend their alms on alcohol or hard drugs. Giving him your spare change is not a humane act, it may keep him on the street.

Why do we so desperately want to show that we love and care for strangers? According to the philosopher Stjepan Mesotrovic, it is because we live in a post-emotional age, one characterised by crocodile tears and manufactured emotion. This, he posits, is a symptom of post-modernity. In a shallow age in which reality and fiction have blurred, in which we are constantly bombarded with news bulletins, soap operas and ‘reality television’, our capacity to feel authentic, deep emotions has withered. In this cynical state, he posits, we no longer want to change the world; we want merely to ‘be nice’.

This is indeed part of the problem, though I believe that conspicuous compassion, more accurately, is a symptom of what the psychologist Oliver James has dubbed our ‘low serotonin’ society. We are given to such displays of empathy because we want to be loved ourselves. Despite being healthier, richer and better-off than in living memory, we are not happier. Rather, we are more depressed than ever. This is because we have become atomised and lonely. Binding institutions such as the Church, marriage, the family and the nation have withered in the post-war era. We have turned into communities of strangers.

Raised in fragmented family units, more and more of us live by ourselves. According to the Office for National Statistics, the percentage of Britons living by themselves in 1971 was 18 per cent; by 2002 it was 29 per cent. Fifty-four per cent do not know their neighbours; 27 per cent say they have no close friends living nearby. Television and the impossible promises of consumerism have cruelly raised expectations of how happy and successful we should be. We are led to believe that buying more products will make our lives complete, and we too will be as content as the women on that advert. We view television as a mirror of reality, and thereby become disheartened that our existence is not as funny as that enjoyed by the protagonists in Friends, as cosy and friendly as those in Cheers or as socially intimate as by those in Coronation Street. As a consequence, depression levels have rocketed in the post-war era.

‘The collapse of marriage and of the close social networks that characterised our ancestors is a major social networks that characterised our ancestors is a major cause of low-serotonin problems: depression, aggression, compulsions’, concludes James in his 1998 work Britain on compulsions’, concludes James in his 1998 work Britain on the Couch, ‘We are supposed to have become a society of Woody Allens, obsessing about trivia and unanswerable philosophical dilemmas to fill the void left by war and plague’. According to the Future Foundation, the proportion of people suffering from ‘anxiety, depression or bad nerves’ has risen from just over five per cent to just under nine per cent in the last ten years. It cites as a reason increased atomisation and the decline in deference for institutions such as the Church, which leave more people with fewer places to seek refuge in times of trial. The State has made divorce far easier, yet divorcees are much more likely to suffer almost every low-serotonin problem than people in intact relationships. The welfare state has helped us become a nation of loners, of single-parents, divorcees, fatherless children. In this regard, James notes:

'Divorce, gender rancour and the isolation of children from depressed or absent parents have all increased since 1950 and between them, play a large role in increasing the numbers of low-serotonin people’.

No wonder we are given to crying in public. And no wonder we seek to do so collectively. Ostentatious caring allows a lonely nation to forge new social bonds. Addition- ally, it serves as a form of catharsis. Its most visible manifestation is the habit of coming together to cry over the death of celebrities or murdered children. We saw this at its most ghoulish after the demise of Diana, Princess of Wales. In truth, the mourners were not crying for her, but for themselves. These deaths serve as an opportunity to (in)articulate our own unhappiness, and, by doing so in public, to form new social ties to replace those that have disappeared.

Such displays are sheer opportunism. They do not reflect, as some contend, that Britain has thankfully cast off its collective ‘stiff upper lip’. They are the symptoms of a cynical nation. To judge by the ‘outpourings of grief’ over Diana in August 1997, one would have thought her memory would have remained firmly imprinted on the public’s consciousness. Yet, on the fifth anniversary of her death in August 2002, there were no crowds, tears or teddies. Diana had served her purpose. The public had moved on. These recreational grievers were now emoting about Jill Dando, Linda McCartney or the Soham girls.

The phrase used to describe this phenomenon, ‘conspicuous compassion’, will for many readers seem merely a play on Thorstein Veblen’s more familiar phrase: ‘conspicuous consumption’. But the two phenomena share more than linguistic similarity. Conspicuous consumption, as Veblen wrote in 1912, is concerned with the leisure class manifesting its position of power through extreme and often deliberately wasteful displays of wealth. Thus, it too is concerned with social one-up-manship. ‘The consumption of luxuries,’ Veblen wrote, is ‘a mark of the master’, and ‘[s]ince the consumption of these more excellent goods is evidence of wealth, it becomes honorific; and conversely, the failure to consume in due quantity and quality becomes a mark of inferiority and demerit’. Similarly, the failure to emote in due quantity and quality becomes a mark of inferiority in our society of conspicuous compassion.

To today’s collective ‘carers’, the fate of the homeless, starving Africans or dead celebrities is not actually of principal importance. What really drives their behaviour is the need to be seen to care. And they want to be seen displaying compassion because they want to be loved themselves. Yet as we will see, sometimes it can be cruel to care.

Patrick West

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario